A stressor brings on a stress response. Stress-related physiological reactions have a consistent pattern.

1. Homeostasis is where we start.

This is a certain kind of cozy, ongoing familiarity, steadiness, or predictability. Imagine that after a satisfying lunch, we are comfortable entering the gym.

2. A stressor that we come across upsets homeostasis.

We begin that challenging workout.

3. Due to the interruption, we enter the “alarm phase.”

We frequently temporarily deteriorate during this phase as we attempt to manage the expectations or dangers. Alternately, maintaining the same level of performance becomes difficult when exercise and activity-related weariness builds.

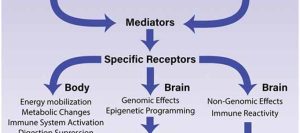

For example: During the workout: We start searching for nutrients in our blood, liver, and muscles because we require fuel. Our heart beats faster to keep up with the need for oxygen-rich blood to reach tissues. As a result, we exhale more rapidly and deeply. The circulation releases stress chemicals such as cortisol and epinephrine (adrenaline). These allow us to release fuel from reserves and turn on our immune system to fortify ourselves against potential harm.

We may have a “fight-or-flight” response if the workout is highly unpleasant or terrifying because our sympathetic nervous system (SNS) revs us up. A surge of energy, nausea, or “shakiness” could be experienced. Following our workout, we might experience fatigue as follows: Our body temperature rises as metabolic waste products accumulate. As a result, our fuel reserves of glucose and glycogen in our blood, liver, and muscles are briefly depleted. As a result, our muscular and central nervous systems use brakes to slow us down (also known as the primary governor or integrated governor response; see the callout box below). We might be thirsty if we lose water through sweating and increased respiration. While we recuperate after the workout, our immune system is briefly (for a few minutes) active before becoming depressed for a few hours. Our muscles and other tissues may undergo minor injury, such as protein breakdown. The inflammatory pathway is activated by inflammatory hormones and cytokines (Proteins involved in cell signaling), which function as “early responders” to deal with this cellular damage and allow us to recover and regenerate tissues.

4. We bounce back and redevelop.

Any tissues that have been harmed will heal and regenerate throughout the following days, provided that we:

Get proper sleep and nutrition, don’t let other pressures build up, and don’t have any other significant illnesses or major health problems (such as a weakened immune system) that make a recovery challenging.

The neurological demands of the exercise will also cause our brain and nervous system to adapt.

This may occasionally entail gaining motor learning (i.e., honing our motor neurons’ ability to move in specific ways). Neurological needs will become crucial when we examine emotional and cognitive stress and recovery.

Our resistance to upcoming shocks increases as a result of this process.

For example, in the long run:

As our mitochondrial efficiency and density increase, we improve our ability to transport energy and eventually become more energetic.

Our immune system gets stronger.

We create new proteins and eliminate the old ones harmed by strengthening our muscles and restoring our glycogen stores.

As cellular waste and debris are removed by our body’s “cleanup crew” (such as macrophages), inflammation is reduced.

We develop more effective and varied movement techniques.

So forth.

5. We establish a new baseline or equilibrium.

We’ve improved a little since then. Therefore, if we recharge and recuperate, we can adapt and improve. Over time, this pattern of ups and downs, stress, and recovery becomes natural, growth-promoting. The stress reaction is typical. It’s our body’s defense mechanism. Our physiological stress response assists us in maintaining attention, energy, and alertness when functioning appropriately. It enables us to rise to adversities. It motivates us to complete tasks even when we might not want to. However, once we reach the point where we can no longer recover on our own, stress ceases being helpful. Instead, it begins chronically harming our bodies, performance, mood, productivity, relationships, and quality of life—all beyond our capacity to recover. Many of your clients’ conduct will be a reaction to stressors. Many customers will approach you when experiencing a crisis, pain, or anxiety. They might have experienced a medical scare, an injury, a breakdown, a transformation in their lives, etc. Whatever the initial stressor, if we were to peer inside the bodies of those individuals, we’d probably see signs of a heightened stress response: more inflammatory molecules, more stress hormones, etc. It’s as though we can “see” the stress in their bodies. However, this is not all. Our conduct frequently changes when our bodies do. When we feel bad, we take action to counteract that feeling. This implies that there will always be some physiological reaction to stimuli. Other reactions, such as thoughts, feelings, or behaviors, will then be sparked by this physiological reaction.

We typically react in ways that are instinctive and protective unless we’ve practiced being wise, effective, and self-aware: fight (or act aggressively), flee (or hide), freeze (or pass out, dissociate, and numb out), and fawn (or try to make ourselves seem less dangerous to others by appeasing and placating them). Understanding these innate stress reactions is essential.

Remember:

“Bad habits” are not merely arbitrary decisions.

They don’t prove that someone is “self-destructive,” “lazy,” or “unmotivated,” either.

As you may recall from Unit 1, these behaviors attempt to deal with stress, anxiety, trauma, overwhelming emotions, or other challenging events. Although “bad habits” (like overeating or drinking) don’t frequently benefit your clients in the long run, they provide temporary respite.